In our previous discussion, we concluded that happiness is living a life of virtue. But this raises two important questions: What exactly is virtue, and how do we live according to it?

What is Virtue?

Aristotle believed that virtue is something we develop through habit. The Greek word for habit, “ethikē,” is where we get the word “ethics.” According to Aristotle, virtue or goodness is something we acquire by repeatedly practicing good actions. He explained this with a few key arguments.

First, Aristotle argued that virtue isn’t something we’re born with; it’s something we learn through repetition. Just like how practicing a skill, like playing an instrument or a sport, makes us better at it, practicing virtuous actions makes us more virtuous. For example, if you practice building houses poorly, you’ll become a bad carpenter. But if you practice building them carefully, you’ll become a good one. The same idea applies to moral virtue: by acting well, we become good people.

The Challenge of Becoming Virtuous

This idea raises a tricky question: If we become virtuous by doing virtuous things, how do we start doing them in the first place? Wouldn’t we already need to be virtuous to do them? Aristotle’s answer is that we can tell if someone has virtue because they take pleasure in acting virtuously. It’s one thing to occasionally do something good, but it’s another to have a character that naturally inclines you to do good and enjoy it.

The “Golden Mean” of Virtue

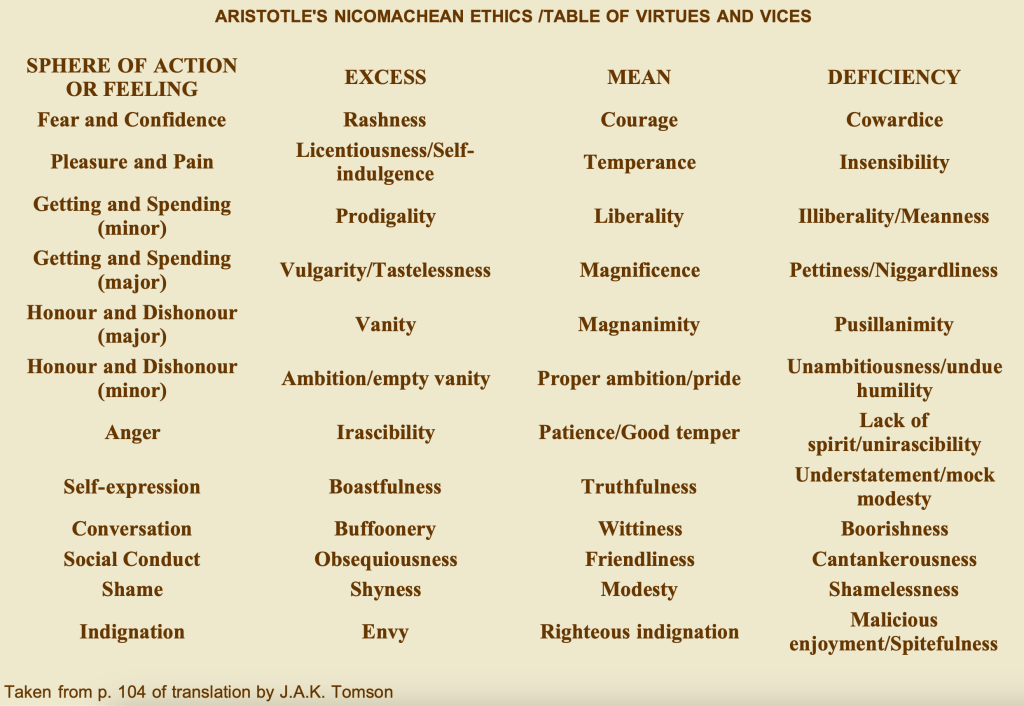

Aristotle defined virtue as a “mean” between two extremes—too much and too little of a trait. For example, courage is a virtue, but too much of it might make you reckless, while too little could make you cowardly. The challenge of becoming virtuous lies in finding this balance, which is different for each person. Achieving virtue is like an art that requires judgment and expertise.

Virtue, Wisdom, and Moral Strength

However, Aristotle argued that virtue alone isn’t enough for happiness. Living a virtuous life requires making choices, which in turn require practical wisdom. Practical wisdom is the ability to make good decisions, but it’s not just another virtue. Unlike other virtues, you can’t have too much practical wisdom. It helps guide your actions but can also be used for bad purposes if misapplied.

In addition to virtue and wisdom, Aristotle believed that moral strength is essential for happiness. Moral strength is the ability to stick to your decisions even when it’s difficult. It’s possible to know what the right thing to do is but still fail to do it because of temptation or fear. Moral strength helps you overcome these challenges.

The Importance of External Goods and Friendship

Aristotle also recognized that internal qualities like virtue, wisdom, and moral strength aren’t enough on their own. We also need external goods, such as enough wealth to meet our needs and good health. Social connections are equally important. Aristotle believed that friendship, in a broad sense, is essential to a meaningful life and to the functioning of society.

He identified three types of friendships: those based on pleasure, those based on usefulness, and those based on mutual goodness. Friendships based on pleasure or usefulness are usually temporary and don’t necessarily contribute to our virtue. However, friendships based on mutual goodness—where both people are good and wish good for each other—are the highest form of friendship. These friendships develop slowly but are long-lasting and deeply meaningful. They support our virtue and contribute to our happiness.

In Aristotle’s view, achieving happiness requires a combination of internal and external factors. Virtue, practical wisdom, and moral strength are essential, but so are material goods and meaningful relationships. Among these, friendships based on mutual goodness are the most valuable, as they help sustain our virtue and make our lives truly fulfilling.

Leave a comment